This is the ninth and final in a series of articles produced for the Future of Work Hub by Lewis Silkin LLP looking at working across borders.

With business increasingly conducted internationally and many organisations deploying staff across the world, issues arising from the management of a global workforce are becoming more complex. For companies confronted with disparate national regulations, there are significant legal challenges. The law has not kept pace with the increasingly global business footprint and employers need to understand and comply with a plethora of issues in order to protect their business against risk when working in different regulatory environments. These range from immigration, tax and social security/pension regimes, to local mandatory laws and systems for dispute resolution.

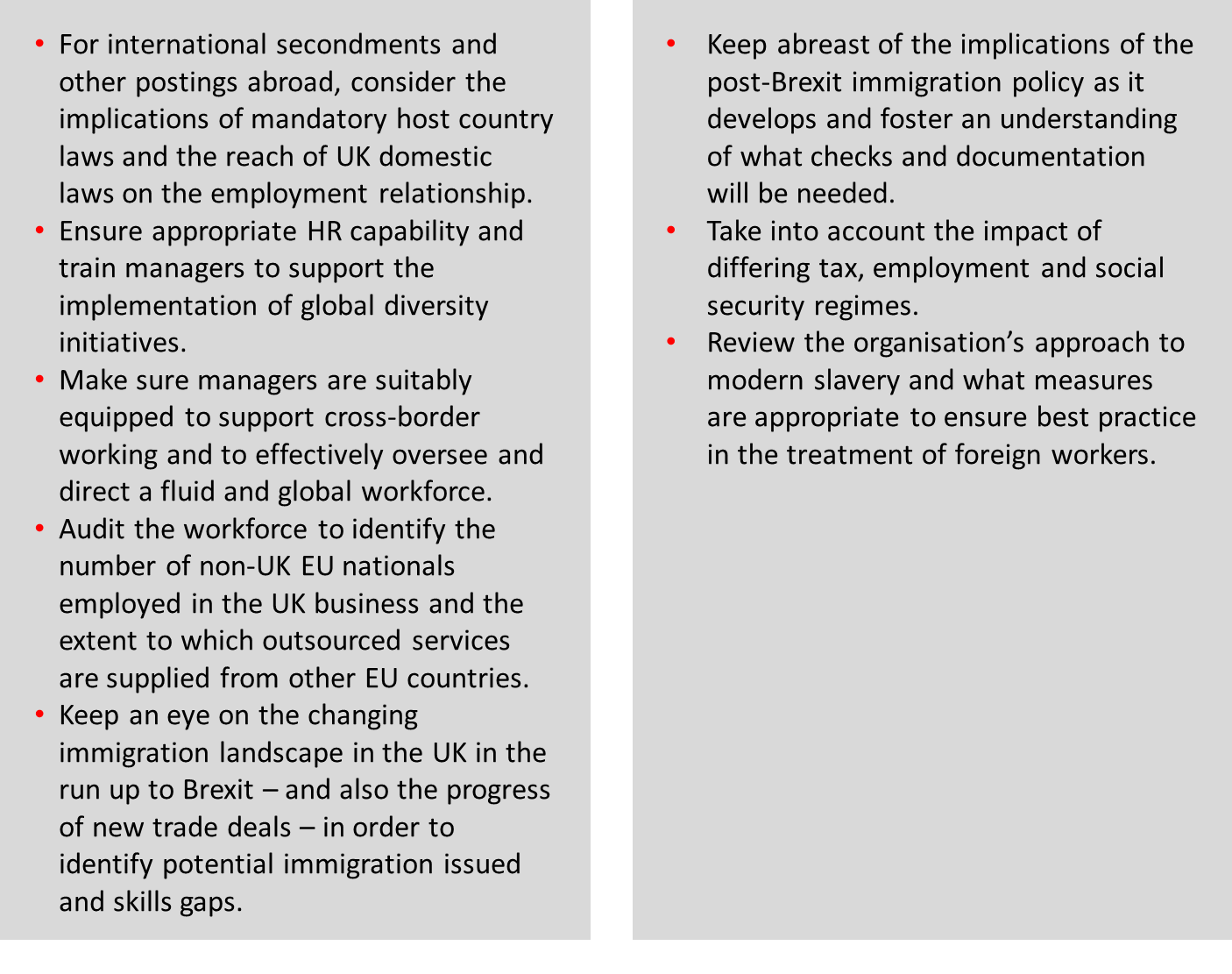

Since the financial crisis, the “expat” model of overseas staffing has dwindled, with organisations increasingly using secondments or engaging peripatetic employees to spend time working abroad for them. Employers need to consider not only how to manage these arrangements in practice, but also how best to reflect them contractually. The challenges of catering for different legal systems that may apply means that a “one size fits all” solution can rarely be applied across a variety of local jurisdictions and it is usually advisable to use contracts specifically adapted for the relevant jurisdiction(s).

A particularly problematic area for multinational employers is how to ensure robust protection of the business by means of restrictive covenants for internationally mobile workers. Approaches to these types of business protections differ significantly between countries, with post-termination restrictions being completely unenforceable in some jurisdictions. At the outset of any international posting, the employer should consider where, in the event of a breach, it will want to enforce any restrictions and ensure that local employment laws are considered at that time.

It is also essential to assess the impact on an international secondment of the host country’s laws, which may grant minimum levels of statutory protection. At the same time, the territorial reach of domestic UK legislation has become increasingly expansive. While neither the Equality Act 2010 nor the Employment Rights Act 1996 - both cornerstones of the UK’s employment law regime - have express jurisdiction provisions, the “substantial connection” test developed by case law can sometimes seem like a relatively low hurdle to overcome for some overseas workers seeking the protection of UK employment law. To avoid creating undue risk, organisations need to ensure a strong understanding of both the mandatory laws of the host country and the application of UK legislation to their peripatetic or internationally mobile employees.

With many organisations operating across international borders, culture and language, the emphasis on greater cross-border understanding has intensified. A sense of shared purpose and culture will become ever more important in bringing together an increasingly flexible and geographically disparate workforce. Managers need to support and develop cross-border cohesion to attract and retain talent, and be equipped with the necessary skills to manage an increasingly fluid and global workforce. Multinational employers seeking to implement global diversity initiatives and policies straddling national boundaries face considerable challenges in striking the right balance. They should reflect the cultural sensitivities and local discrimination laws, which vary in each jurisdiction, while at the same time strive to achieve a consistent global position. Effective communication and training are essential to ensure successful adoption of the initiatives that are decided upon.

Companies operating in numerous international locations also need to consider how to deal with the differing rights of its workforce in the relevant jurisdictions. Family leave rights and entitlements, for example, vary extensively across the globe. Treating employees differently in different countries poses tricky employment relations issues. To address this, some multinational companies have made strategic moves to introduce mandatory minimum global family leave entitlements which they essentially “level up” for their global workforce. While these types of arrangements are far from the norm, more employers managing complex cross-border workforces are likely to follow suit in order to help attract and retain talented staff.

In light of the global competition for talent, it is essential for organisations to be able to deploy their workforce across borders in order to respond to changing demands. For many employers, immigration has a fundamental role to play in meeting challenges of low productivity, underemployment and widening skills gaps, but Brexit will change the UK’s migration landscape significantly. The UK needs high levels of immigration in many sectors – such as retail, agriculture, construction, retail and hospitality – due to an insufficient number of UK workers who are prepared to accept those jobs at their current pay rates. Although raising salaries might attract more UK workers, this would make goods and services more expensive and exports less competitive.

The government has stated that the free movement of people between the EU and the UK will end in March 2019. From that date, EU workers moving to the UK will be required to register, at least until any permanent post-Brexit immigration policy is put into place. In light of this, organisations should review their workforce from a number of perspectives. Where functions have been outsourced to EU countries, Brexit may make operating in those locations more difficult and expensive in the future. Organisations currently relying heavily on non-UK EU nationals may find that post-Brexit immigration restrictions make their current model more challenging, requiring them to reconsider how best to meet current and future skills gaps. Although a significant number of current EU workers in the UK are likely to be able to apply for indefinite leave to remain and stay permanently, there is considerable uncertainty. EU workers and their employers will need to understand the limitations of their new status in the UK. Organisations will also have to ensure they are employing EU workers lawfully in a post-Brexit world, in order to avoid illegal worker penalties.

The darker sides of globalisation have included the exploitation of labour and a growing gap between rich and poor. Fiercer competition has led many businesses to subcontract foreign labour pools, offering access to cheaper and more flexible work. Practically, it is almost impossible for many businesses to maintain oversight of their geographically diverse and increasingly complex supply chains. This has had catastrophic effects on the rights of many workers, reflected in the many labour tragedies of recent years. These include, to name just a few examples, the death of over a thousand workers at the Rana Plaza garment factory in Bangladesh, widespread wage bondage in the South East Asian electronics trade and the exploitation of African and Asian migrant workers in fishing trawlers. In the UK, following intensive efforts this year, the National Crime Agency reported that modern slavery and human trafficking are more prevalent in the UK than previously thought.

The response to this has been a slowly growing trend towards formal and informal measures to protect global labour rights. We are beginning to see the development of national legislative frameworks that aim to address the exploitation of foreign workers. For example, the UK’s Modern Slavery Act - Europe’s first law against modern slavery – was introduced in 2015. It requires commercial organisations with a global annual turnover of at least £36 million to produce a slavery and human trafficking statement for each financial year.

Companies are also increasingly taking matters into their own hands by applying national policies at a global level to ensure good practice in the treatment of foreign workers and implementing commercial measures to protect foreign labour in their supply chains. Such initiatives have come about partly because of the growing importance of a business’s ethical brand power in an expanding marketplace that is becoming ever more competitive in terms of attracting and retaining both talent and consumers. Millennials, actively engaged by ethical concerns, are driving corporate social responsibility up the business agenda.

Non-legislative bodies are also doing what they can to implement enhanced cross-border rules and protections. Over recent years, both the British Standards Institute and the Society of Human Resource Management in the US have been working on international global HR standards.

FUTURE DEVELOPMENTS

There is no doubt that the relationship between globalisation, migration and skills will continue to develop, requiring organisations to face up to operational and strategic challenges when working across borders.

Research by Goldman Sachs predicts that BRIC economies may become as big as the G7 by 2032 and the Chinese economy will match the US economy by 2027. Asia is likely to account for about 60% of middle-class consumption by 2030 and PwC predicts that within 30 years the majority of the world’s largest industrial clusters will be located in markets that we currently regard as “emerging”.

Commentators seem divided over whether cross-border business barriers will continue to disintegrate, or whether nations will become increasingly isolationist to protect national business interests. The UK’s vote to leave the EU and the Trump presidency in the US are arguably straws in the wind suggesting the latter. Further significant moves towards de-globalisation would most likely lead to laws and legal systems drifting further apart rather than coming together, creating a challenging environment for employers working across borders in the coming years.

The changing nature of the UK’s relationship with the EU will impact on the available talent pool and organisations’ ability to recruit and move employees between countries to meet business needs. As part of workforce planning, employers should review how Brexit (and potential new free trade deals with the US, Australia and others) will affect their workforce.

CHECKLIST

Watch out for the next article in the series will look at managing technology, personal data and privacy. To read the introduction to the report which gives an overview of the impact of three megatrends - globalisation, technology and changing demographics - on the world of work, see the introduction to the series.

If you would like an advance copy of all sections of the report "Future Proofing Your Business", click the button below to let us know.